Land Call to Learn & Act

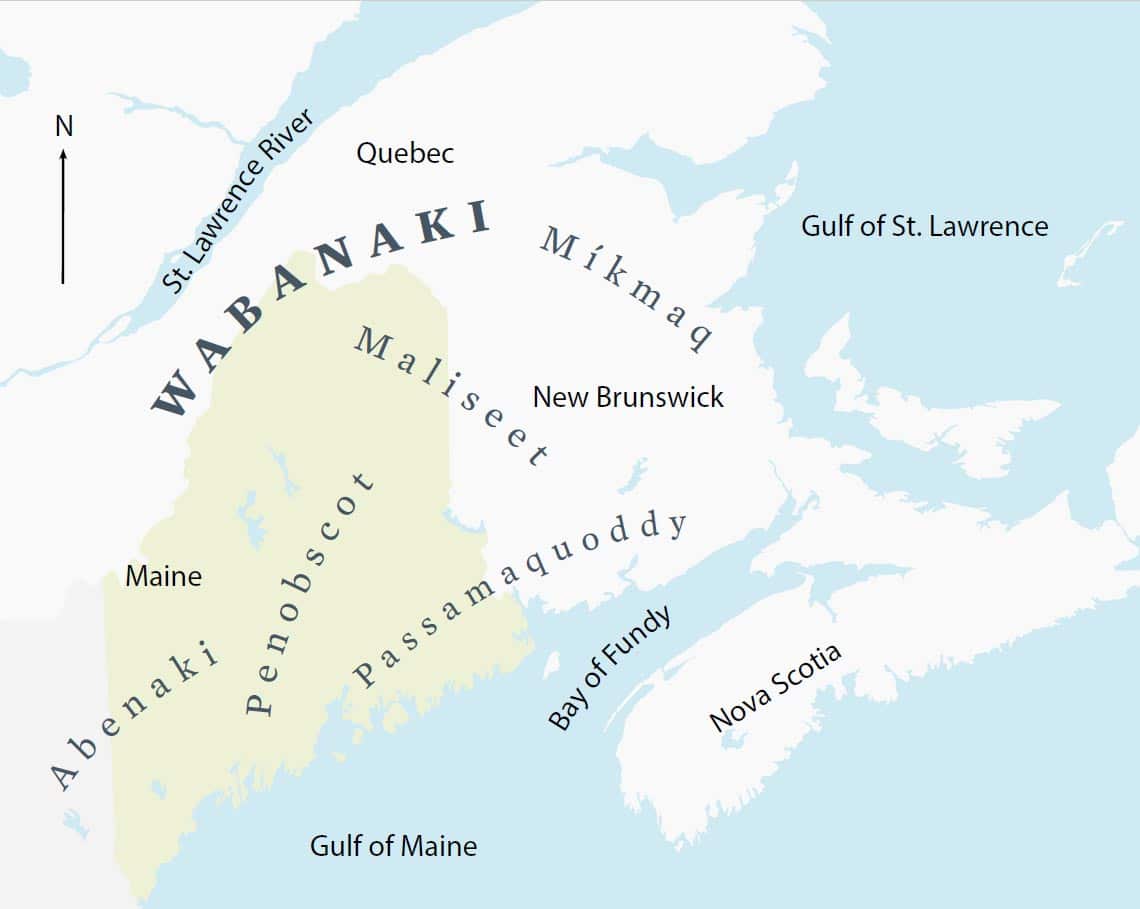

The work of the Local Foods Action Plan Lewiston Auburn (LFAP LA) takes place on unceded Abenaki Territory. The region is part of the broader homelands of the Abenaki, Mi’Kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Maliseet Nations for more than 12,000 years. The work thus far of the LFAP LA has not impactfully centered Wabanaki land rematriation or food sovereignty actions. Under the Goal to Increase Land Access and Justice in the updated plan, LFAP Leads will be prioritizing access pathways for restoration of Wabanaki sovereignty and reciprocal land relationships, including cultural food and spiritual use, as part of efforts to permanently secure community gardens or other comparable growing sites across Auburn and Lewiston. One existing community garden in Auburn, Newbury Garden, along the “Little Androscoggin River,” is recognized as an important site by the Abenaki.*

The Androscoggin River, recorded and known as Ammoscongan among Abenaki, was vital life-giving kin- like all rivers in this land- for generations of Wabanaki. The area in and around the river at the “Great Falls” in downtown Auburn and Lewiston was known as Amitgonpontook or “the place to dry or smoke the fish at the falls.” Families and communities would travel from Merrymeeting Bay, Quabacook, known as “the place for hunting ducks” and stop to fish at the falls at Pejepscot (today’s Brunswick) and then eventually Amitgonpontook.

Continuous communities of Wabanaki were violently displaced from their homelands along Amitgonpontook, as were all of Maine/Wabanakik, through centuries of attempted genocide by European settlers. One such violent massacre perpetuated by the English occurred in what is now called Auburn in 1690 at a Abenaki planting village adjacent to and/or possibly including parts of what is the Newbury Community Garden.

LFAP Coordinators hold this history seriously alongside the truth that despite all that has sought to erase Wabanaki, members of all 5 tribes continue to live in and tirelessly protect their homelands, fight for their sovereignty and preserve, steward, and re-enliven their culture, knowledge, and traditional foodways. In holding this history and this truth, LFAP Coordinators and Leads are exploring pathways that can be pursued within the context of the plan that will ultimately lead to relationship building, repair and rematriation along the Ammascongan.

We will use this page to provide honest updates and milestones but also as a place to continue community learning about what it means to act on behalf and in solidarity with Wabanaki

*This work will only be pursued with the full participation and consent of Wabanaki land protectors. Some initial communication with Wabanaki leaders has been initiated by LFAP Coordinators, with more work yet to do.

Map of Wabanaki Territories. Maine State Museum.

LEARN

- Native Land Map

- Wabanaki Place Names of Wester Maine (Interactive)

- Wabanaki Place Names of Western Maine (Printable)

- Abbe Museum

- Bomazeen Land Trust

- Land in Common

- Houlton Band of Maliseet

- Mi’kmaq Nation

- Nibezun

- Niweskok

- Passamaquoddy Tribe at Indian Township

- Passamaquoddy at Sipayik

- Penobscot Indian Nation

- Wabanaki Commission on Land and Stewardship

- Wabanaki Reach

ACT

Calls to Act will be periodically updated as new priorities emerge from Wabanaki land rematiration efforts across the region

Support Niweskok in closing on farmland in Swanville! Donate here: https://www.niweskok.org/donate

@niweskok on Instagram

Wabanaki Non-Profit Close to Having a Home at Swanville Farm! Niweskok, a local non-profit of Wabanaki farmers, land tenders and educators, is under contract and raising funds towards purchasing a 245-acre working farm near Belfast in coastal Penobscot territory. They have worked diligently to raise half of the purchase price in a few short months. This farm will provide a home for Niweskok’s mission of restoring the Penobscot Bay region as a Wabanaki food hub incorporating their work of traditional crop cultivation, land-based education, and fisheries revitalization. Currently Niweskok’s food projects are spread across borrowed, leased, public, and trust lands, sometimes hours away from their homes. With the lack of a base, Niweskok had to pause infrastructure development and growth opportunities that they are now poised to reignite and expand, creating a stable foundation for long-term community impact and sustainable land stewardship in an area where Wabanaki have been excluded.